POLLY WALKER

|

CREATING A NEW STORY

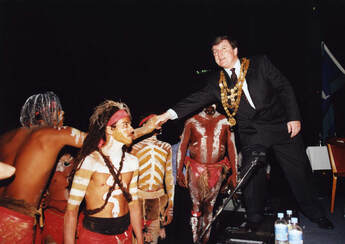

"Let us work at this relationship. It's not just a one-time ceremony. It's a way of life." - Ray Levesque, Two Rivers Centuries after colonization took place in Australia and the U.S., conflict lingers in the memories of the past and in the present-day realities of Indigenous and Settler peoples. Polly Walker describes how conflict transformation occurs through memorial and gathering rites. Contemporary ritual, incorporating traditional practices and cosmological beliefs, leads to group action for ongoing reconciliation and restorative justice. |